The preceding posts covers “A C19 Sextant Restoration” , “Making a Keystone Sextant Case” , “Restoring a C. Plath Drei Kreis Sextant” , “Heath Curve-bar sextant compared with Plath” , “A Drowned Husun Three Circle Sextant” and “Troughton and Simms Surveying Sextant” .

It is seldom that I can afford distinctive instruments except by buying homeless wrecks and restoring them, but recently I was able to acquire a genuinely antique sextant at a price that left both me and the seller happy. I had seen it on the local auction site, TradeMe. It attracted no bids. It was relisted the following week and attracted only one bid, mine, that did not reach the reserve price. A few weeks later, I invited the seller to relist with a fixed price offer. Happily, I was able to afford the asking price, but the matter did not end there, as I was suspicious from the rather poor photographs, that the sextant might turn out to be from M’bai (Bombay), rather than from the putative maker, Henry Hughes. I did not want to part with my money without seeing the sextant “in the metal” and the seller did not want to part with the sextant without seeing the colour of my money. We had a slightly one-sided compromise: she travelled 80 km north and I travelled 200 km south to a meeting.

It turned out that the sextant was not by Henry Hughes, though it had a bedraggled Husun certificate in the case, suggesting that it was still in use sometime after about 1920, when the Husun trade mark came into use. Engraved on the limb was the worn and barely visible inscription “King’s Patent. GILBERT & Co. Tower Hill. LONDON.” John Gilbert was a noted C18 instrument maker who at the time of his death in 1791 was working from 8 Postern Row, Tower Hill, in the shadow of the infamous Tower of London. The firm continued as Gilbert and Son and merged with another noted instrument maker in 1808, when the firms became Gilbert and Gilkerson. An identical sextant named “Gilbert and Son” is illustrated in Figure 48 of Peter Ifland’s book “Taking the Stars” and has been given an approximate date of 1790. I think mine is probably dated between 1791 and 1808, and I would be glad to hear from anyone who can date it more closely. Here are front and rear views as the instrument came to me (most of the photos will withstand a lot of enlargement. Click on the picture to enlarge. Right click outside the edge of the picture and select <Back> to return to the post)

Fig 1 Front view

Fig 2 Rear of sextant

It had lost nearly all trace of whatever paint it once had, or perhaps an owner had followed the all-too-common practice of stripping the paint and polishing all the “brass”, something that I think makes a once-powerful instrument look forlorn, rather like a woman without her false teeth or a man without his trousers. Happily, the arc had not been polished, and the divisions looked sharp and clear:

Fig 3 Detail of arc and limb

As there was no trace of tarnish, nor of polishing of the arc or adjacent brass, I briefly wondered whether it might have been divided on platinum, but there is no sign of an inscription “platina”. If it is of platinum, and only time and perhaps the application of a little mustard will tell (it will turn silver black), it would make its date no earlier than 1804, when William Wollaston first isolated it in commercial quantities and probably not earlier than 1808, when makers like Edward Troughton applied it to sextants. (See Postscript no. 1)

This venerable sextant has many interesting features that the owner of a modern sextant will never see outside a museum. I certainly felt a little like an industrial archeologist, as I uncovered little clues that gave me insight into the mind of the eighteenth century instrument maker.

Starting with the frame, it is a bronze casting, rather slender by modern standards, while the limb, of brass 1.92 mm (0.075 in) thick, appears to have been attached to the frame by nine rivets, the head of one of which can be seen just to the right of the figure 50 in Figure 3, above. More likely, it was first sweated on, a process in which each surface is “tinned” with soft solder and then reheated with the surfaces pressed in contact. This would have been followed by drilling and tapping for countersink-headed screws, whose heads would then have been filed off flush. The next photo, which shows how relatively slender is the bronze frame, gives us an idea of the small diameter of the screws. With modern taps, made of high speed steel, tapping would be a task needing great care to avoid the disaster of a broken tap. One wonders how many eighteenth century apprentices earned a whipping for breaking a crude tap of the era. Compared to a modern tap, the steel would have been of uncertain quality, with the thread and flutes ill-formed. Looking at the screws used, every one made by hand, they have very fine and shallow threads (48 threads per inch, sometimes more), as a coarser or deeper thread would need more effort to cut it. In fact, forming a thread in brass was more of a moulding than a cutting process.

Fig 4 Structure of frame

As close examination of Figure 1 will show, the silver arc does not extend right to the ends of the limb. This is a most unusual feature which suggests that the undercut slot for the arc was formed before the limb was attached to the frame. It could not otherwise have been cut, as dovetail milling cutters, still less milling machines, had not by then been invented and it would have been nearly impossible to form with chisel and files. Both earlier and later sextants, where the arc extends to the ends of the limb, would have cut the slot by turning the part on the lathe, but as the radius of the arc is 192 mm (7.56 in) the intermittent cut would have presented a challenge to the lathes of the day. Possibly, the ends of the slot were filled in with a sliver of brass after setting in the arc. (See Postscript no. 2)

The arc itself, nearly always of silver, would start as a strip of metal, which would then be rolled into a semi-circular section and be hammered into the slot before being filed off flush. Silver is used because until the middle of the nineteenth century sheet brass was an uncertain material, produced by hammering with a broad faced hammer and by rolling, followed by rubbing on or with an abrasive stone, so that it would have many hard spots that could divert the scriber of the dividing engine from its true path (Figure 5, showing the underside of the index turntable shows the chatter marks as a hand-held turning tool argues with a tenacious material). Unfortunately, because silver is soft, polishing rapidly wears away the divisions, and it also tarnishes rapidly in a sulphur rich atmosphere like coal-fired industrial areas. The arc should never see silver polish. Tarnish can be removed by careful wiping with dilute ammonia solution.

Fig 5 Chattering under the table

The flat surface for the attachment of the horizon mirror and the index shades is again of 1.92 mm brass sheet, attached to the frame by seven screws, whose heads reside in counterbores. The next photograph, of the front of the naked frame, shows that the region of the horizon mirror is also supported by an extension of the frame, to the side of which the horizon shades are attached by two screws. A similar extension supports the telescope mounting.

Fig 6 Front of frame

Finally for the frame, there is an unusual triangular brace, again of sheet brass, attached to the back of the frame by five brass screws (two of which had lost their heads), reinforced at the corners by the screw-in legs and the middle screw of the unusual handle (Figure 2). The latter is attached at the middle as well as the usual top and bottom, and has a threaded socket about 10 mm diameter for an extra handle, which must have made taking horizontal angles and lunar distances a good deal more comfortable. A sextant named Gilbert and Wright in the National Maritime Museum in Greenwich (F5183) has a similar bracing that forms a diagonal cross, but the frame of this sextant appears to be much more slender and to be lacking the middle of the transverse bars. It is not clear to me whether the bracing served any useful purpose in my sextant, and other makers do not seem to have copied the practice.

The threads of one leg had all but stripped and the other one was bald and the leg seemed to be held uncertainly in place with something like Araldite. Thus, jobs for the frame included machining off the threaded portion of the legs, fitting in a new piece and cutting a thread on it, and drilling and tapping the holes to fit the new thread. There was no question of copying the old threads, as there was no standardisation much before the middle of the nineteenth century. I used 4 BA threads for the legs. There were also two headless screws that had once secured the brace to the frame. The remains of the screws had to be filed flush, centre popped, drilled out and retapped, and I had to make new screws to match the remaining ones. Number 9 BA seemed to be about the right size. I was very thankful that a friend had recently given me a full set of BA taps and dies, as the odd sizes are rather hard to come by.

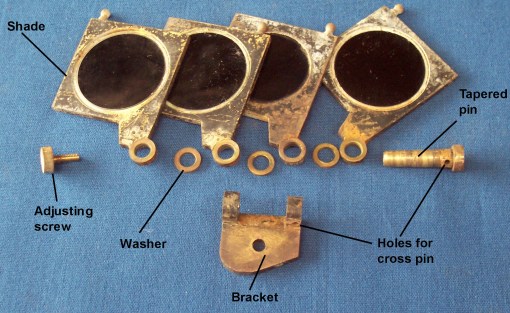

The index arm and its bearing was next for attention. A tapered shaft attached to the upper expanded end of the index arm runs in a bearing that fits closely in a hole at the apex of the frame. Bearing play is taken up by moving the shaft axially into the bearing by means of an adjusting screw on the end of the shaft operating through a washer. The end of the shaft is squared to fit a square hole in the washer so that latter rotates with the shaft and cannot loosen the screw. This design did not change at all during the next two centuries.

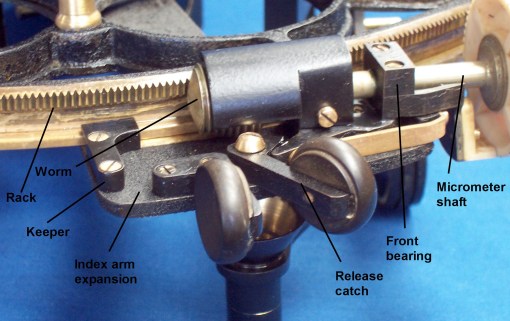

In many sextants, including this one, the end of the shaft is enclosed in a cover. The index arm between the top and the expanded bottom is stiffened by a central rib which is attached by means of six small screws. A pillar for the arm of a Ramsden scale magnifier is mounted about two thirds of the way down. At the lower expanded end of the index arm is a standard extended vernier scale reading to 30 seconds and a conventional tangent screw and clamp. The latter was missing its spring, though one of the original attaching scews was still present.

As so far described, the index arm showed no change for as long as vernier sextants were produced. This sextant is slightly unusual (but not unique for the period) in that the vernier scale is attached to the upper side of the window in the expansion. At the upper end, however, the index mirror is not attached directly to the index arm. Instead there is an intermediate turntable which rotates on an extension of the bearing shaft and is secured to it by a screw that sits in a counterbore in the turntable. At the top end of the turntable is a lug which allows small adjustments to be made to the position of the turntable to which the index mirror is attached. In short, it is a rather elaborate method of adjusting out index error. The next three figures may make this clearer.

Fig 7 Turntable bearing

Fig 8 Turntable adjustment

Fig 9 Index mirror mounting

The index mirror is mounted in a way that became pefectly standard and is probably due to Peter Dolland. In a letter that he wrote to Neil Maskelyne, the Astronomer Royal in 1772, he wrote “…I have contrived the frame, so that the glass lies on three points, and the part that presses against the front of the glass has also three points exactly opposite the former.”The method of rotating the index mirror on a turntable may be what is referred to by the words “Kings patent” on the limb, granted to Peter Dollond in May 1772 for ” …adjusting and improving the glasses of Hadley’s…sextant…” . It is possible that it refers as well to the method of adjusting the horizon mirror for side error, about which more later.

Figure 10 Broken journal

As I have already mentioned, the index arm bearing was entirely conventional, but on removing the cover, I found some “repairs” had been carried out: someone had broken the head off the original screw and crudely replaced it with a modern self-tapping screw. On further dismantling , the Araldite that had been used in the “repair” to attach the shaft to the flange that marries it to the index arm gave way. You see the result in Figure 10. I had to attach a new piece of brass to the flange (Figure 11), taking great care to maintain squareness and then turn the journal to match the existing taper of an included angle of about 0.8 degrees (Figure 12). Those interested can Contact me to find out how I set up the lathe to cut this rather fine taper. I then milled the square on the end of the shaft (Figure 13). This is easily and precisely done with modern machinery, but the eighteenth century instrument mechanic would have used a file and filing rest to do the same job and probably in much less time than it takes me to set up the machine.

Fig 11 Journal repair 1

Fig 12 Journal repair 2

Fig 13 Journal repair 3

Generally, I would strongly advise repairers against removing the bearing from the frame, but in this instance, the rear end of the bearing had been damaged during the original “repair” so it had to be faced off in the lathe. It was inserted from the back and was a very tight push fit, so to maintain the original centring I had only to replace it in the same orientation as it was originally, paying great attention to cleanliness. Removing it also gave me the opportunity to observe traces of black lacquer hidden beneath it, thus confirming me in the view that these instruments were supplied as painted workaday instruments and not as shiny display pieces.

Design of the tangent screw and clamp was standard for the day and again remained unchanged until the demise of the vernier sextant (Figure 14). The leaf spring would have been made of a thin sheet of brass, “well-hammered” to work harden it and make it springy. I took a short cut and used a piece of modern hard brass, first sweating it to the clamp, before drilling and tapping new holes for two screws. Note that the tangent screw knob slides on a square on the end of the screw, the standard method of the day to remove backlash at the bearing, though no provision was made to remove it at the bronze nut as well.

Fig 14 Tangent screw and clamp

There is nothing unusual about the mounting of the shades, except that all the washers are free to rotate on the tapered shafts, while later designs adopt some means to stop them rotating, so that when one shade is rotated into place, the movement is not transmitted to the adjacent ones. The design of the rising piece is also unremarkable for the time and was followed with various more-or-less complicated minor modifications until the mid 1950s.

This leaves the horizon mirror and its mounting. Peter Dollond’s patent of 1772 (number 1017) mentions improvements to mirror mountings. In a letter of the same year to Nevil Maskelyne he writes: “To adjust the horizon glasses in the perpendicular plane of the instrument, I have contrived to move each of them (there was also a “back horizon glass” that soon fell into disuse with the increasing popularity of the sextant) by a single screw, that goes through the frame of the quadrant, and is turned by means of a milled head at the back, which may be done by the observer while he is looking at the object.” His letter also makes plain that horizon shades were an innovation devised by Maskelyne.

The next photo (Figure 15) shows the arrangement in place. The screw passes through the frame into a tapped hole in the base of the mirror mounting and is used to tilt the horizon mirror in such a way as to remove side error, as index error has been taken care of by the index turntable, but note also that there is a capstan headed screw which can also deal with index error. Perhaps it was a later addition, the index turntable having been found wanting.

Fig 15 Dollond's adjusting screw 1

Although Dollond gives no details, the hole through the frame of the sextant is much larger than required for the screw alone, and I surmise that there must have been a helical spring to take up backlash at each end of the screw. However, the screw is threaded almost to the milled head and it is possible there may have been some sort of locknut arrangement to hold the screw captive, since lost. While the spring seems to be obvious solution, there are other possible simplifications to the design of this sextant that also seem obvious to us in the light of two centuries of hindsight, but which plainly were not so to the instrument makers of the late eighteenth century. Figures 16 and 17 make clear the design of this curiously complicated solution.

Fig 16 Dollond's adjusting screw 2

Fig 17 Dollond's adjusting screw 3

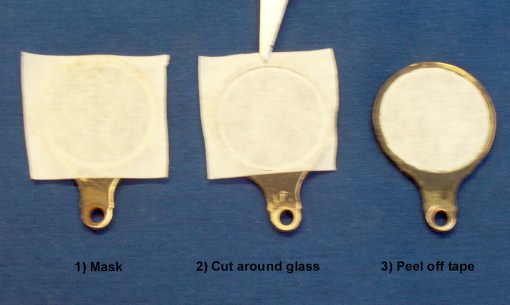

While some museologists might regard it as heretical, I try to restore my instruments to the way they might have been when fairly new, perhaps just out of the instrument maker’s shop after an overhaul. This usually includes repainting with something as close to pre-modern paint as possible. Modern paint seems to be much too thick and I use a black lacquer, which gives a very pleasing finish. Most of the screw heads would have been polished and their slots cleaned out, following clock-making practice. I will allow that the telescopes were probably polished rather than painted. The next two pictures show the finished instrument from front and back. These imges will withstand considerable enlargement if you wish to see more detail.

Fig 18 Finished, front

Fig 19 Finished, rear

Both Figs 18 and 19 show the outside of the case, which was in quite good condition and responded well to fine sanding and a coat of wax. One of the hooks and its eye were missing, and their holes had been closed off with pink car body filler. I made fairly close copies of the hook and eye by sawing and filing them out of plate brass, and think they will pass at least casual inspection. I made the octagonal handle out of a piece of unidentified New Zealand hardwood, stained and polished, and let in a piece of brass rod, threaded to fit the hole in the back of the handle, I secured it in the handle with a transverse piece of brass rod. Used as we are to hexagonal nuts and bolts, we might wonder why handles of this type were octagonal. I suggest that it is firstly easier to make, by planing off the corners of a square, and secondly, while a hexagon is easily held in a three jaw self-centring chuck, such chucks had not come into use in the eighteenth century and if a turner possessed a chuck at all, it was likely to have four independent jaws, better adapted to holding an octagon than a hexagon.

The final picture shows the sextant in its case. The telescope is not without interest. It is a Galilean or “star scope” of about 3 power and with an objective lens of only 14 mm in diameter. Newton’s rings are clearly visible when looking at the objective, showing that it is an air-spaced achromatic lens, as lenses were not cemented until well into the nineteenth century. Its small size is probably because large pieces of good flint glass were hard to obtain. The eyepiece is threaded for an eyepiece shade, but there is no accommodation for one in the case.

The name of Dollond arises again in relation to achromatic objectives. John Dollond is often cited as the inventor of this type of lens, even though it is well established that Chester Moor Hall was making them for himself in 1729 and it was well known to the optical trade by the middle of the century. Nevertheless, John’s son Peter urged him to take out a patent and in this he was successful, against staunch opposition from about thirty of the leading London opticians. There is a link to Jesse Ramsden, the inventor of the first precision circular dividing engine. Ramsden is thought to have tried to put the record straight and he was in a good position to know it, as his wife was Peter Dollond’s sister. There is a space for an inverting telescope, which would have been about 140 mm long and of probably about 6 power.

The case itself is of mahogany and it is interesting to note that the bowed front is not a segment of a circle but its radius increases towards the right, so that the sextant will fit in the case only if the index arm is parked close to zero. This appears to be so of many early sextant cases and was presumably deliberate.

A question which will occur to some might be “How accurate is it?” This will have to wait for another time… (See Postscript no. 3)

Fig 20 Restored sextant in restored case

I hope this rather lengthy description of an old sextant will be of interest to lovers of fine instruments as well as contributing to the record of instrument making. I cover in detail the structure of sextants from about 1850 onwards in my book “The Nautical Sextant” , jointly published by Paradise Cay and Celestaire. Contact me if you would like to buy a copy directly from me (probably only worthwhile for New Zealand and Australian readers).

Postscript no. 1: It later occurred to me that platinum is harder than silver. On the Vickers scale of hardness, it is about twice as hard. I made a new business end for an automatic centre punch to give it an included angle of 135 degrees and set up the punch so that it delivered a constant blow when actuated. The size of the tiny punch mark made in the end of the scale was of the same size as that made in an arc known to be of silver. The conclusion is that the Gilbert arc is the same hardness as silver. If it looks like a duck…

Postscript no. 2: On careful examination with magnification and the right light, a rivetted screw head is just visible in the brass at the left hand end of the arc. My surmise that a slip of brass was rivetted in after machining the groove for the silver arc seems to be correct.

Postscript no. 3: The errors are as follows:

Degrees Error, arcseconds

15 +6

30 +2

45 -3

60 +10

75 +6

90 +3

105 +24

120 +25

See more details at http://www.fer3.com/arc/m2.aspx?i=113271

Figure 8 : Calibration table and graph of errors.

Figure 8 : Calibration table and graph of errors.

You must be logged in to post a comment.